🔎 Mutation-selection models

Mutation-Selection codon model, what are they and what are their use cases?

Introduction

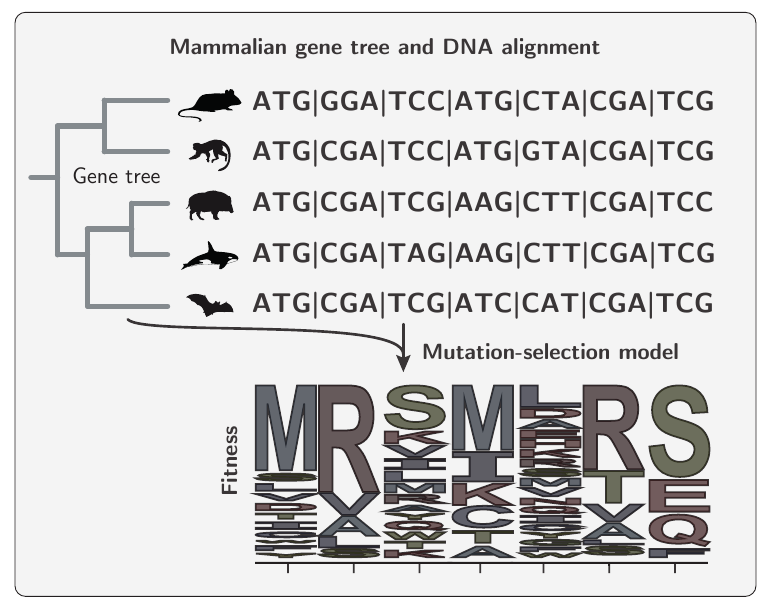

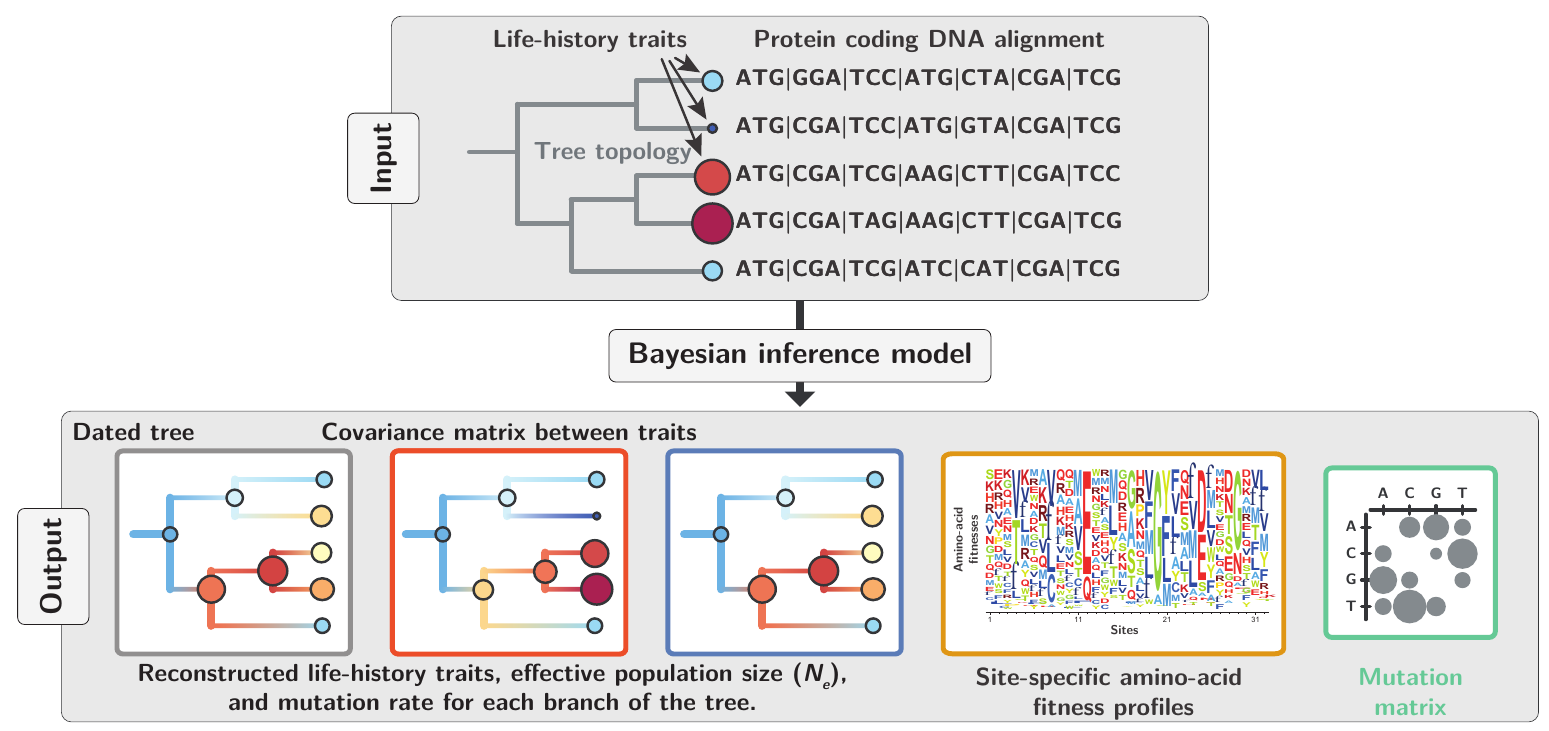

From an input/output perspective, mutation-Selection codon model take as input a phylogenetic tree and a protein-coding DNA alignment, they output site-specific fitness profiles, i.e. the fitness of each amino-acids at each site:

They are codon models, meaning they contrast non-synonymous and synonymous substitution rates along the phylogeny to estimate the strength of selection exercised on proteins.

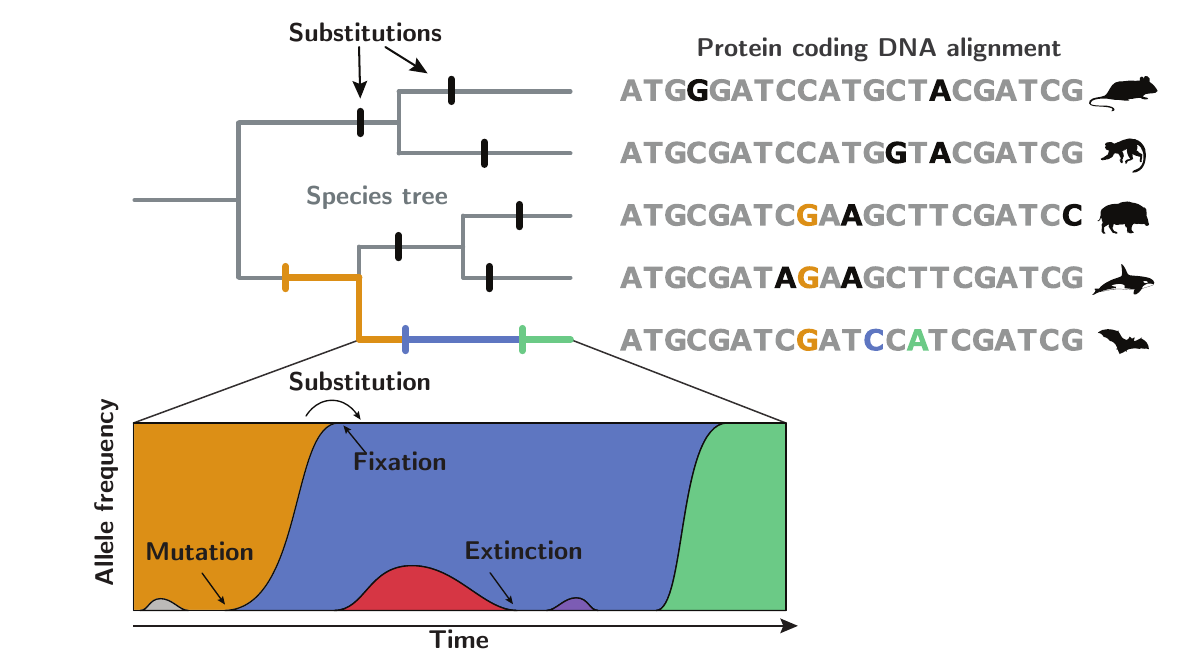

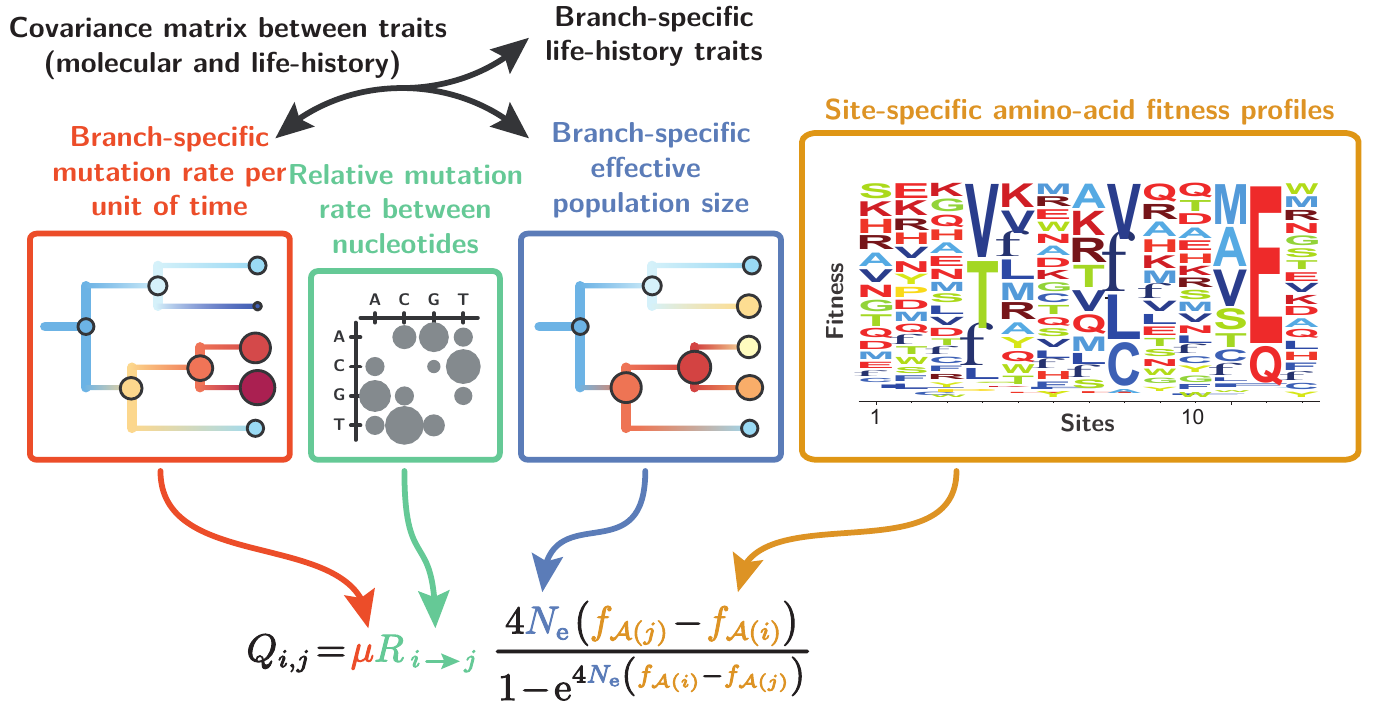

Mathematically, they are based on population-genetic formalism, by collapsing the trajectory of alleles inside a population into a single point substitution process:

Model

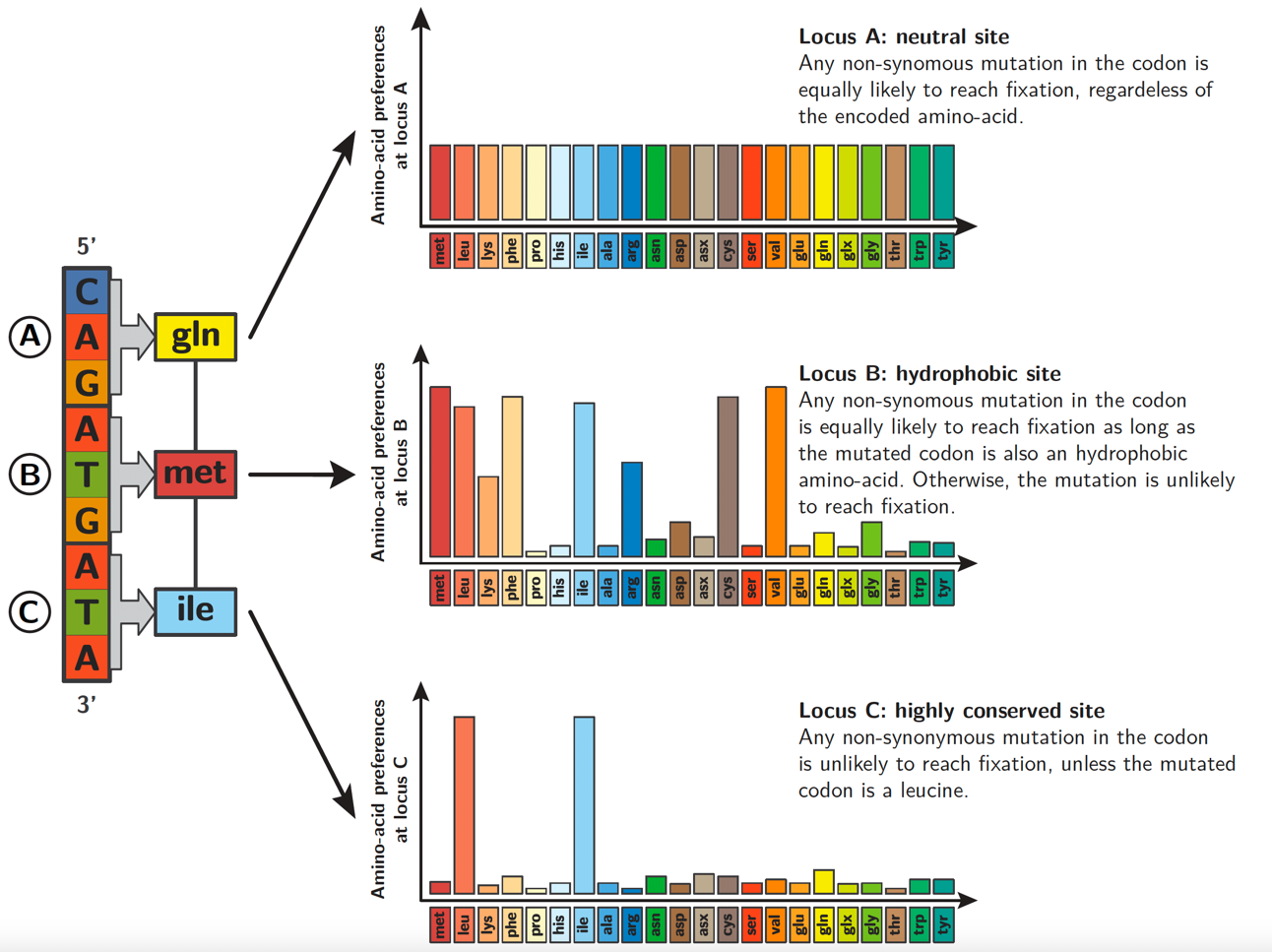

These models assume the protein-coding sequences are at mutation-selection balance under a fixed fitness landscape characterized by a fitness vector over the $20$ amino acids at each site.

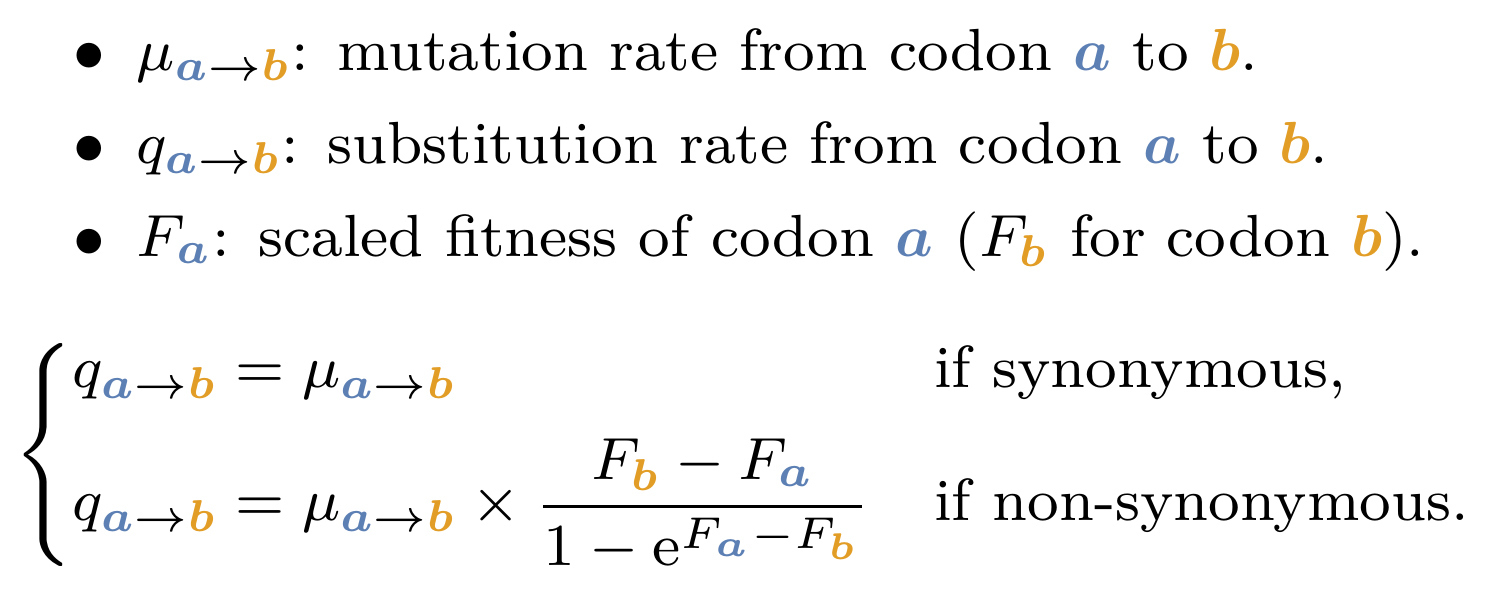

Mathematically, the rate of non-synonymous substitution from codon $a$ to codon $b$ $(q_{a \mapsto b})$ at each site of the sequence is equal to the rate of mutation of the underlying nucleotide change ($\mu_{a \mapsto b}$) multiplied by the scaled probability of mutation fixation ($P_{a \mapsto b}$).

The probability of fixation depends on the difference between the scaled fitness of the amino acid encoded by the mutated codon ($F_b$) and the amino acid encoded by the original codon ($F_a$) at each site:

From a methodological perspective, fitting the mutation-selection model on a multi-species sequence alignment leads to an estimation of the gene-wide $4 \times 4$ nucleotide mutation rate matrix ($\bm{\mu}$) as well as the $20$ amino-acid fitness landscape ($\bm{F^{(i)}}$) at each site $i$.

In our implementation, the Bayesian estimation is a two-step procedure.

The first step is a data augmentation of the alignment, consisting in sampling a detailed substitution history along the phylogenetic tree for each site, given the current value of the model parameters.

In the second step, the parameters of the model can then be directly updated by a Gibbs sampling procedure, conditional on the current substitution history.

Alternating between these two sampling steps yields a Markov chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) procedure whose equilibrium distribution is the posterior probability density of interest.

Additionally, across-site heterogeneities in amino-acid fitness profiles are captured by a Dirichlet process.

More precisely, the number of amino-acid fitness profiles estimated is lower than the number of sites in the alignment.

Consequently each profile has several sites assigned to it, resulting in a particular configuration of the Dirichlet process.

Conversely, sites with similar signatures are assigned to the same fitness profile.

This configuration of the Dirichlet process is resampled through the MCMC to estimate a posterior distribution of amino acid profiles for each site specifically.

From a more mechanistic perspective, even though not all amino acids occur at every single codon site of the DNA alignment, we can nevertheless estimate the distribution of amino-acid fitnesses by generalizing the information recovered across sites and across amino acids based on the phylogenetic relationship among samples.

In particular, synonymous substitutions along the tree contain the signal to estimate branch lengths and the nucleotide transition matrix, while non-synonymous substitutions contain information on fitness difference between codons connected by single nucleotide changes.

Use cases

Since such models are based on population-genetic formalism, it can be used to study the interaction between mutation, selection and drift.

Mutation

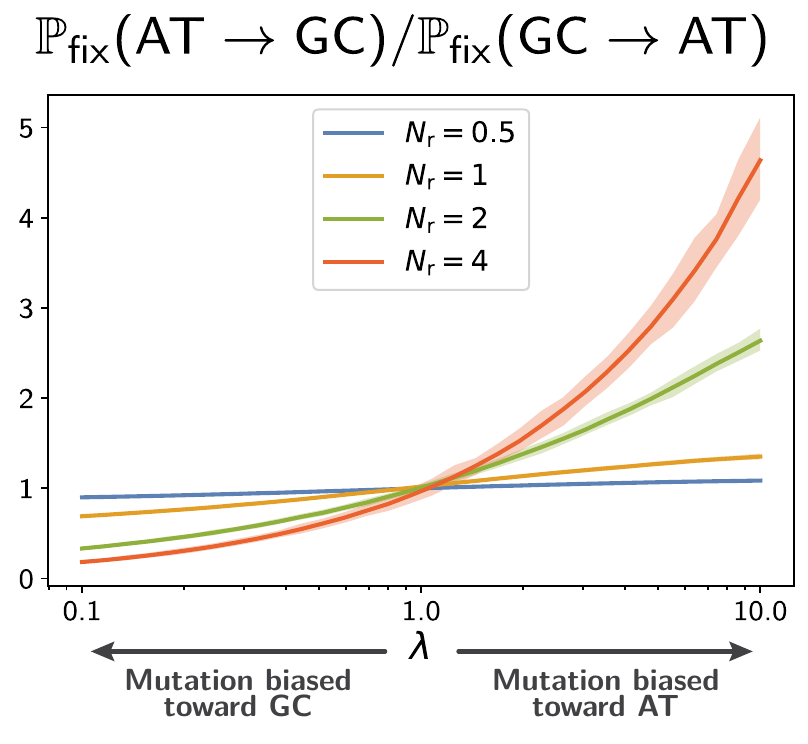

Mutation and selection are opposed to each other at the mutation-selection equilibrium.

A mutation bias toward AT will push the gene to be “too” AT-rich (because of drift), and selection will favor mutation toward GC, in the opposite direction.

Selection

Given the estimates of site-specific fitness profiles ($\bm{F}$), we can first predict which amino-acids are favored at each site, and each one are deleterious. First, we showed that fitness effects of mutations estimated at the phylogenetic scale with mutation-selection models can predict the fitness effects of mutations in extant populations (see notes on fitness prediction across scales).

Second, we can predict the expected rate of evolution of a protein at the mutation-selection equilibrium: ω₀. Sites evolving faster than expected under the mutation-selection equilibrium are deemed to be under adaptation (ω>ω₀), as described in this paper. From those estimation of adaptation at the phylogenetic scale, we showed that genes under adaptation across mammals also exhibit recent adaptation in several species and populations (see notes on gene adaptation across scales)

Drift

Mutation-selection models can be used to infer changes of effective population size (strength of drift) along the phylogeny. Thus far, they have relied on the assumption of a constant genetic drift, translating into a unique effective population size ($N_e$) across the phylogeny, clearly an unrealistic assumption.

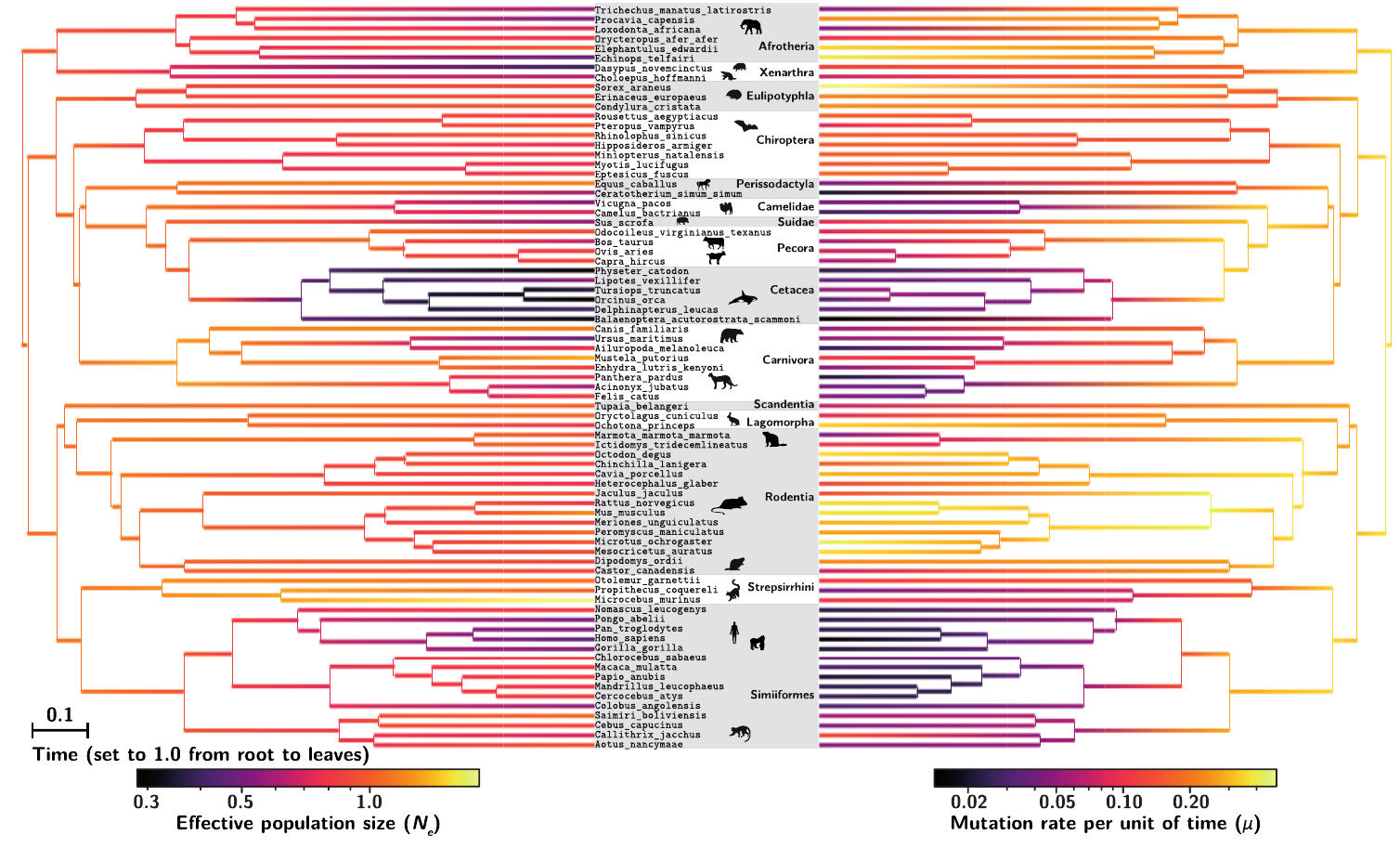

This assumption can be alleviated by introducing variation in $N_e$ between lineages. In addition to $N_e$, the mutation rate ($μ$) is susceptible to vary between lineages, and both should covary with life-history traits (LHTs). Slower rate of evolution along branches is interpreted as an increase in selective pressure, thus larger population size (e.g. bats). In this direction, we introduce in this paper an extended mutation-selection model jointly reconstructing the fitness landscape across sites and long-term trends in $N_e$, $μ$, and LHTs along the phylogeny.

This model is fitted from an alignment of DNA coding sequences and a matrix of observed LHTs in extant species.

The model was tested against simulated data and applied to empirical data in mammals to obtain changes in effective population size ($N_e$) and mutation rate ($μ$) along the phylogeny:

The reconstructed history of $N_e$ in these groups appears to correlate with LHTs or ecological variables in a way that suggests that the reconstruction is reasonable, at least in its global trends. On the other hand, the range of variation in $N_e$ inferred across species is surprisingly narrow. This last point suggests that some of the assumptions of the model, in particular concerning the assumed absence of epistatic interactions between sites, are potentially problematic.

Software

A Bayesian implementation and instruction/documentation of a mutation-selection framework available at https://github.com/ThibaultLatrille/bayescode, with a conda package also available (conda install -c conda-forge -c bioconda bayescode).